Thanks JSD.JavaScriptDonkey wrote:Sorry I missed this request Steve.stevecook172001 wrote:Show me the FRB regulations that limit the capacity of commercial banks to lend money they don't have

The BIS Basel 3 regulations should have that covered.

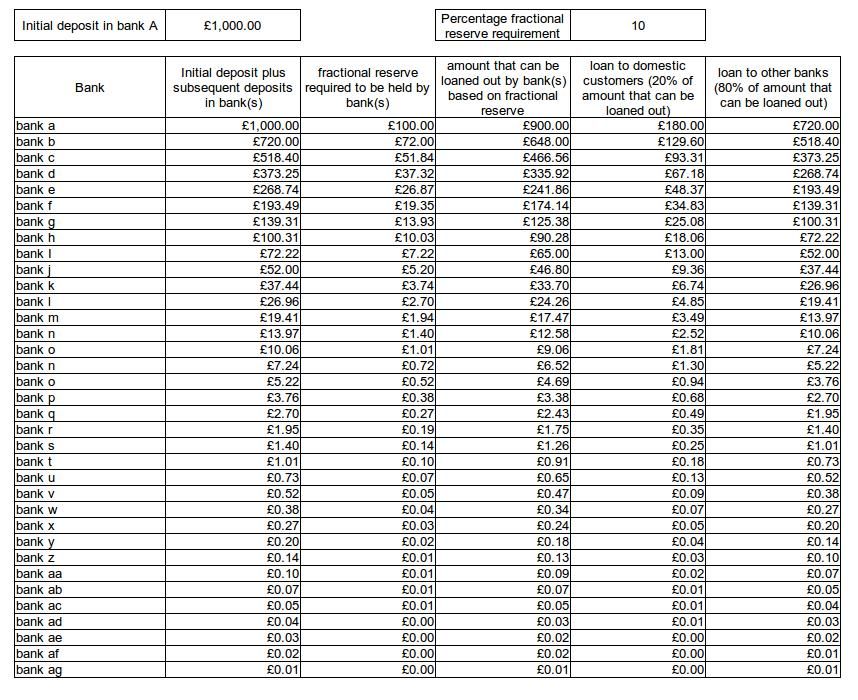

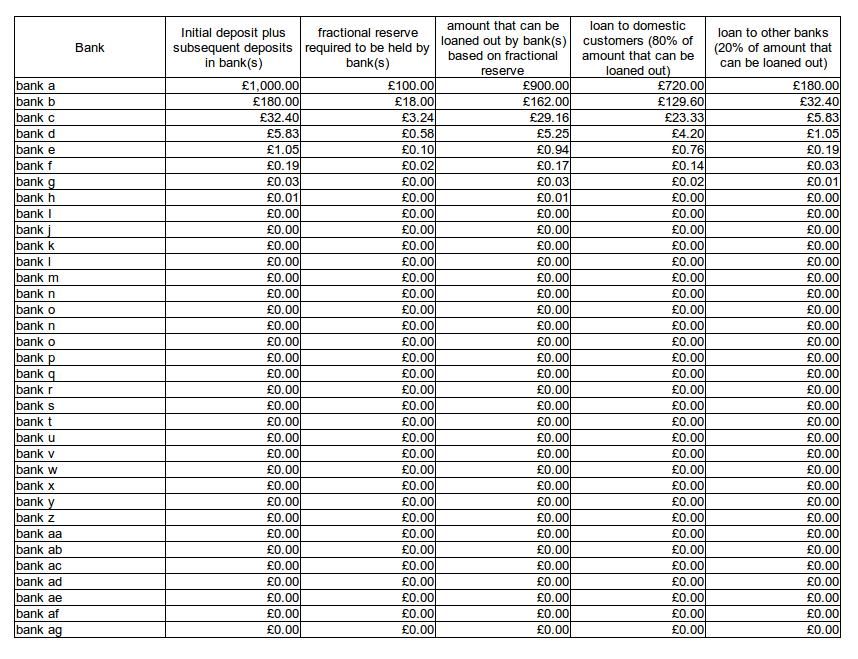

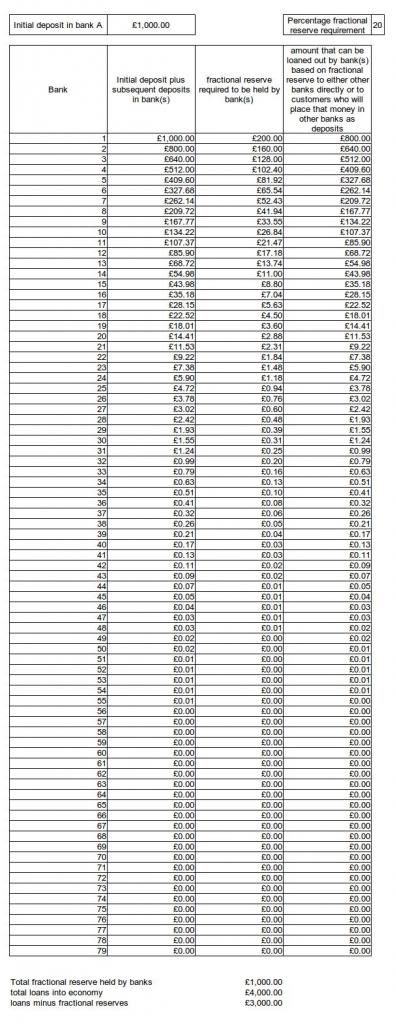

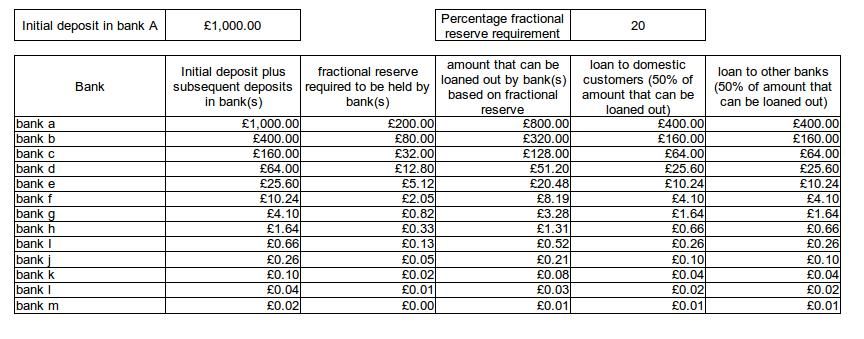

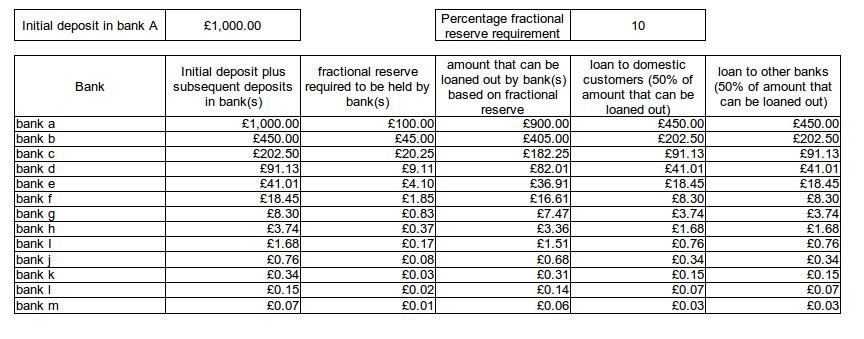

I have drawn up a table:

The above table is based on each bank having a fractional reserve requirement of 20% and splitting the amount they can loan back out equally (50%) between domestic customers and other banks (who each have their own 20% fractional reserve requirement).

Based on the above analysis;

The total amount held on deposit by all of the banks in the table = £333.33

The total amount lent out into the economy by all of the banks in the table = £666.66.

The total loans into the economy + the total held on deposit by the banks = £1000 (give or take a penny due to round-ups).

So, if the entire banking system is limited to a given fractional reserve of say, 20% then there can be no more money in the system (held in both deposits and money lent into the economy, than was the case in the beginning.

Additionally, it doesn't matter what the fractional reserve is set at, the money on deposit plus the money on loan always adds up to the £1000. All that happens is more or less of it is on deposit or loan. It also doesn't matter what the ratio of lending from banks is with regards to other banks or domestic customers, For example, if the fractional reserve is set to 10%, the numbers come out thus:

However, this still begs the question of how the money supply increases over time since it is demonstrably larger than it was, say, 50 years ago or even 20 years ago.

Well, one way that happens is if national banks borrow off other banks from overseas to raise their deposit on account (and fractional reserve), thus allowing them to lend more out to domestic customers). This means that international money can end up being concentrated in one particular region of the world, thus fuelling debasement of the value the money in that region if that money does not have a suitable home to go to in the economy.

Another way is for banks to borrow it off their central banks. If the central bank raises their money via government bonds, then this is just another way of transferring money form overseas and concentrating it in another given region. They then promise to pay back their international creditors in due course.

All of which does not explain how the global money supply rises over time. All that has happened in the above analysis is that money has been sloshed around within an economy via banks and across economies via banks and central banks.

So how has the money supply actually risen over time JSD?

If anyone else cares to comment on these tables, I'd be grateful