This is the point of divergence, I think. The interest on loans isn't taken out of the money supply it's spent back into the economy (albeit more slowly). The money in circulation does not expand because of interest it expands because there's more money needed for economic activity. Or rather it's predicted that there will be. So point two of divergence, there will not always be a certain multiple of base money in circulation - Mark already mentioned that the ratio has changed significantly in the past - this is because money supply is not determined by reserve ratios it's determined by the predicted value of assets, i.e. debtors. That's what I took from what JSD said, so I rather felt that the kicking he just got was ill-deserved.stevecook172001 wrote: However, the interest is another matter that really. The only way that is accounted for is by the issuance of new base money.

The future of money

Moderator: Peak Moderation

-

Little John

No wait, nothing you have said there denies the existence of the money multiplier.AndySir wrote:This is the point of divergence, I think. The interest on loans isn't taken out of the money supply it's spent back into the economy (albeit more slowly). The money in circulation does not expand because of interest it expands because there's more money needed for economic activity. Or rather it's predicted that there will be. So point two of divergence, there will not always be a certain multiple of base money in circulation - Mark already mentioned that the ratio has changed significantly in the past - this is because money supply is not determined by reserve ratios it's determined by the predicted value of assets, i.e. debtors. That's what I took from what JSD said, so I rather felt that the kicking he just got was ill-deserved.stevecook172001 wrote: However, the interest is another matter that really. The only way that is accounted for is by the issuance of new base money.

I need to go over this again to see where exactly we disagree, because what you are writing here does not make that clear at all.

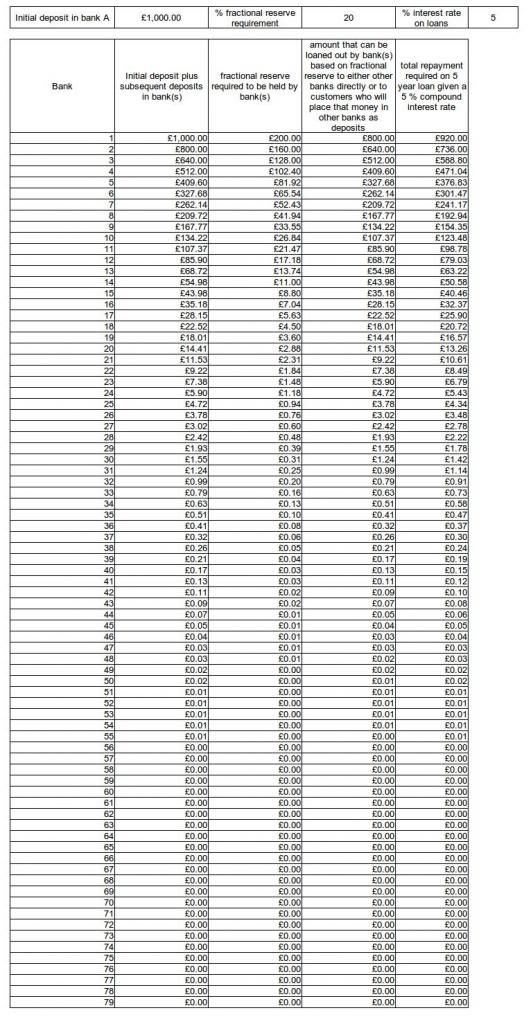

As I am sure you are aware, the banks must operate on a fractional reserve ratio. That is to say, they can only lend out a fraction of the deposits they hold. However, this only make sense of the deposits they hold are, themselves, real money. The problem is they are not. I need to include a few tables to show how this works.

The above is an example table showing how an initial £1000 created by a Central bank and then placed in Bank A, cascades down through the banking system being lent out over and over again. This is because the lendings of one bank are allowed to be used as the deposits of other banks. I have emboldened this last sentence because it is the key.

Of course, each time the money enters the next bank in the chain, a bit is shaved off the amount that can subsequently be lent out because some of the debt-based deposit must remain on the deposit side of a given bank's books. The process of re-lending out of the same money only stops when infinity is approached.

So, starting from a baseline figure of 1000 central bank money, we end up with a situation where the total amount of "money" in the system is £4000 (due to banks effectively using the debt side of other banks' balance sheet as the deposit side on their own balance sheet) and that the debt based monetary system must actually grow over the next 5 years by another £600 just to make the books balance at the end of that period. This is because of the compound interest applied to the loans.

The only way the above can be made to work is if the central bank continues to lend money into the system to cover the hole in the balance sheet implied by interest rates on loans. But, of course, the banks are simply going to multiply lend out any new money that comes into the system and so the problem keeps on growing.

All of the above is the reason why governments shit themselves when growth stops because, when that happens, the ponzi-scheme money-supply promptly collapses. However, they can't allow it to collapse and so they keep pushing money into the system regardless. The trouble is, this new money no longer has an economic home to go to (due to halted growth) and so merely has the effect of causing inflationary driven prices rises due to the oversupply of money. This is why recessions often bring inflationary price rises with them instead of deflationary collapses in prices, which is what one might have intuitively expected.

In the above example, the central bank base money supply will need to grow to £1150 in 5 year's time to cover the interest repayments on the loans and this means that there is a built-in requirement that the economy will grow by 3% per year for each of those 5 years to accommodate the extra money flowing into the system. Any growth less than that and you end up either with deflation (if the CB does not create enough base money) or inflation (if the CB does create the money). The only way you avoid either inflation or deflation is if the economy grows by just the right amount. Whatever happens, the economy must perpetually grow in order for this type of FRB-based money-supply to work.

In short, an FRB-based money-supply is always a car-crash waiting to happen and on a finite planet of finite resource you can be guaranteed it will happen (due to the limits to growth implied by those finite resources).

On the ground in the real world, of course, things are more complicated. But the principles outlined above still hold. for example, I have shown with the above schematic how the money must go from bank to bank to wring out all returns. However, the money that is lent out by a given bank on the debt side of its balance sheet, could just as easily receive that money back itself as a deposit. In other words, it the lent out money doesn't have to actually go to another bank. Or, another way to look at it is to say that it doesn't matter if the money does go to another bank because somebody else's money is going to come to this bank.

In addition to all of the above is the influx of money that has originated outside of a given monetary jurisdiction. This only serves to further exacerbate the problem. But, again, none of this is evidence of the money multiplier not existing.

If you would deny the existence of the money multiplier as I have outlined above, please be specific about with part of the process you think does not exist or does not exist in the form I have described. Or, if there is any part I have not explained sufficiently, let me know and I will try again.

I just knew a wall of text with tables was coming up. Your example says that fractional-reserves don't impose a limit on how much can be loaned or how much money is in circulation. Those controls are pretty much history anyway, so we don't care. So what does limit how much money is loaned? Oh yes, the number and creditworthiness of debtors - the bank's actual assets - and value of other assets like property.

We're not interested in how money deposited in another bank can be used as part of that bank's reserves, because as we've already seen that doesn't impose a limit anyway. The total 'created' money will always match the total debt. The money supply does not need to grow to pay the interest on the loans as the interest on the loans should be recirculated into the economy. Plus a given number of those loans fail at any time giving you a situation where the money supply can go both up and down. (If memory serves the Great Depression saw money supply reduced by something like 30%. Not fact checked that but I'm pretty sure it went down).

In short I think you have the cart before the horse. More money in circulation is not a driver for growth, growth is the driver for there being more money in circulation.

We're not interested in how money deposited in another bank can be used as part of that bank's reserves, because as we've already seen that doesn't impose a limit anyway. The total 'created' money will always match the total debt. The money supply does not need to grow to pay the interest on the loans as the interest on the loans should be recirculated into the economy. Plus a given number of those loans fail at any time giving you a situation where the money supply can go both up and down. (If memory serves the Great Depression saw money supply reduced by something like 30%. Not fact checked that but I'm pretty sure it went down).

In short I think you have the cart before the horse. More money in circulation is not a driver for growth, growth is the driver for there being more money in circulation.

Just thought of an example which might clear up the disagreement. In your example you have £1000 of CB/Government money and £3000 debt based money. Imagine banking stops, all loans are repaid and that £3000 is destroyed. £600 is paid to the banks from the CB money in circulation.

How much money is now in circulation? a) £400 b) £1000

How much money is now in circulation? a) £400 b) £1000

-

Little John

My example precisely does place limits on how much is lent out. I can't believe you have missed that. The limit is set by the fractional reserve. With a fractional reserve of, say, 20%, the multiple limit is 3 times the original base money. If the reserve is changed, the multiple limit is commensurately changed. The upshot of all of the above is that while individual banks my have a reserve of, say, 20% such that they can only lend out 80% of their deposits, the banking system as a whole has a limit which is vastly higher and so actually lends out 300% of its deposits.AndySir wrote:I just knew a wall of text with tables was coming up. Your example says that fractional-reserves don't impose a limit on how much can be loaned or how much money is in circulation. Those controls are pretty much history anyway, so we don't care. So what does limit how much money is loaned? Oh yes, the number and creditworthiness of debtors - the bank's actual assets - and value of other assets like property.

We're not interested in how money deposited in another bank can be used as part of that bank's reserves, because as we've already seen that doesn't impose a limit anyway. The total 'created' money will always match the total debt. The money supply does not need to grow to pay the interest on the loans as the interest on the loans should be recirculated into the economy. Plus a given number of those loans fail at any time giving you a situation where the money supply can go both up and down. (If memory serves the Great Depression saw money supply reduced by something like 30%. Not fact checked that but I'm pretty sure it went down).

In short I think you have the cart before the horse. More money in circulation is not a driver for growth, growth is the driver for there being more money in circulation.

As for your point about total created money equalling the total debt, well yes of course it does. What has that got to do with denying the existence of the money multiplier? Additionally you then go on to say that growth drives money creation and not the the way around. This is an important but non-directly connected issue to the specific point about the money multiplier effect. So, why cite it here as evidence of the money multiplier not existing?

Nothing you have written here denies the existence of the money multiplier effect. You have simply made some unrelated points about the money supply and then gone on to say the multiplier process does not exist. I am bound to say I am getting the distinct feeling you are beginning to obfuscate here.

Point out specifically where, in the process I have outlined, it is wrong and why. No vagarious please. Be specific.

-

Little John

Your question is flawed because all of the money in circulation has been lent into the economy at interest. The loans can't all be repaid with interest all in one go because there simply isn't enough money in circulation.AndySir wrote:Just thought of an example which might clear up the disagreement. In your example you have £1000 of CB/Government money and £3000 debt based money. Imagine banking stops, all loans are repaid and that £3000 is destroyed. £600 is paid to the banks from the CB money in circulation.

How much money is now in circulation? a) £400 b) £1000

The original CB base money has to reside in the banks as their fractional reserves. All of the money actually in circulation is debt that has been lent off the back of the original base money.

Bear in mind, when I say the above, I am saying it schematically. That is to say, it doesn't actually matter whether you call some of the money in circulation or on bank deposits bank money or CB money. The point is that in total the money adds up in the way I describe and so schematically it is logically true that the CB money is on deposit whilst the money in circulation is chequebook money. If the entire system was boiled down in the kind of way you describe by all loans being cleared, this is precisely what would pertain.

Except, of course, it wouldn't because of the interest applied to the loans

I don't think I have been vagarious, but I'll try this statement: Neither fractional reserve banking nor interest force exponential growth in the money supply. Clear? You seem to disagree with that statement, correct me if I'm wrong.stevecook172001 wrote: Point out specifically where, in the process I have outlined, it is wrong and why. No vagarious please. Be specific.

If you quibble with the figures from my interest example would a system with £1000 held as deposits, £1000 government generated money in circulation and £3000 in loans charging £600 in interest be stable? Illustrative of the perils of oversimplification if nothing else.

-

Little John

You are deliberately trying to turn the question of the existence of the money multiplier into another question. Those are related, but separate questions. You now have done this sufficiently enough times to allow me to plausibly conclude it is deliberate obfuscation on your part. The fact is, you still have not dealt with a single specific point of fact of the maths in my example of the multiplier effect nor of the fact of the existence of the multiplier in the actual banking system, save to simply deny it's existence.AndySir wrote:I don't think I have been vagarious, but I'll try this statement: Neither fractional reserve banking nor interest force exponential growth in the money supply. Clear? You seem to disagree with that statement, correct me if I'm wrong.stevecook172001 wrote: Point out specifically where, in the process I have outlined, it is wrong and why. No vagarious please. Be specific.

If you quibble with the figures from my interest example would a system with £1000 held as deposits, £1000 government generated money in circulation and £3000 in loans charging £600 in interest be stable? Illustrative of the perils of oversimplification if nothing else.

I am forced to conclude you have failed to do so because you are unable to do so. However, I am happy to stand corrected should you decide to do so.

Do you deny the existence of the money multiplier in the banking system or not? If you do, you will need to be specific in your denial of the maths in my example. It is perfectly possible to to answer this question irrespective of any of the diversionary points you have made.

As is stands, though, given the apparent lack of willingness so far to answer this question with the example provided to you, I won't hold my breath.

Oh for pity's sake - every time something comes along that disturbs your world view you accuse the source of being an agent of disinformation. You've done it to me far too often to be taken seriously yourself.

This is what I understand by money multiplication in your own words

This is what I understand by money multiplication in your own words

This is the bit I disagree with (mostly - the rest is a bit shaky as well, but this is the big one)Of course, each time the money enters the next bank in the chain, a bit is shaved off the amount that can subsequently be lent out because some of the debt-based deposit must remain on the deposit side of a given bank's books. The process of re-lending out of the same money only stops when infinity is approached.

So, starting from a baseline figure of 1000 central bank money, we end up with a situation where the total amount of "money" in the system is £4000 (due to banks effectively using the debt side of other banks' balance sheet as the deposit side on their own balance sheet) and that the debt based monetary system must actually grow over the next 5 years by another £600 just to make the books balance at the end of that period. This is because of the compound interest applied to the loans.

The only way the above can be made to work is if the central bank continues to lend money into the system to cover the hole in the balance sheet implied by interest rates on loans. But, of course, the banks are simply going to multiply lend out any new money that comes into the system and so the problem keeps on growing.

The only possible reason I can think of for there being any confusion is if you're taking the definition of money multiplication to refer to the statistic: commercial bank money/CB money. That does not appear to be your argument. (If I'm being unkind the argument you're making appears to be that the ratio of commercial bank money/CB money exists therefore the money supply must grow exponentially).the debt based monetary system must actually grow over the next 5 years by another £600 just to make the books balance at the end of that period

-

Little John

BollocksAndySir wrote:Oh for pity's sake - every time something comes along that disturbs your world view you accuse the source of being an agent of disinformation. You've done it to me far too often to be taken seriously yourself.

This is what I understand by money multiplication in your own words

This is the bit I disagree with (mostly - the rest is a bit shaky as well, but this is the big one)Of course, each time the money enters the next bank in the chain, a bit is shaved off the amount that can subsequently be lent out because some of the debt-based deposit must remain on the deposit side of a given bank's books. The process of re-lending out of the same money only stops when infinity is approached.

So, starting from a baseline figure of 1000 central bank money, we end up with a situation where the total amount of "money" in the system is £4000 (due to banks effectively using the debt side of other banks' balance sheet as the deposit side on their own balance sheet) and that the debt based monetary system must actually grow over the next 5 years by another £600 just to make the books balance at the end of that period. This is because of the compound interest applied to the loans.

The only way the above can be made to work is if the central bank continues to lend money into the system to cover the hole in the balance sheet implied by interest rates on loans. But, of course, the banks are simply going to multiply lend out any new money that comes into the system and so the problem keeps on growing.

The only possible reason I can think of for there being any confusion is if you're taking the definition of money multiplication to refer to the statistic: commercial bank money/CB money. That does not appear to be your argument. (If I'm being unkind the argument you're making appears to be that the ratio of commercial bank money/CB money exists therefore the money supply must grow exponentially).the debt based monetary system must actually grow over the next 5 years by another £600 just to make the books balance at the end of that period

You have still not made it explicitly clear why you think the money multiplier as I have outlined is incorrect. At least you have come some of the way to identifying which part you disagree with. So, that's progress, I suppose. I'm going to break this down into a series of easy to understand questions. I would be obliged if you were able to provide a clear answer to each of them. Let's take this one step at a time in order to establish precisely which bit you take specific issue with and why:

1) Do you accept that central banks create base money for our economy either by buying it in from outside the system via the issuance of government bonds or, if they wish, by directly creating it from scratch with mechanisms such as QE.

2) Do you accept that the banks who take out loans of base money from the CB can then lend out a proportion of it to other banks and/or non-banks customers based on their fractional reserve requirements?

3) Do you accept that either:

non-bank customers are either going to deposit the money they have borrowed into a bank or are they going to spend the money such that the recipient (or some recipient at some point down the chain of transactions) is going to deposit the money into a bank, thus allowing the recipient banks to declare that loaned money that has been deposited with them on their books as a part of their assets and thus increase their fractional reserve?

or

other banks who have directly borrowed the money from the first bank in the chain are going to be able to declare their loaned money as an asset on their books and thus increase their fractional reserves?

4) Do you accept that in either or both instances of (3), the increased fractional reserves of the banks having received previously loaned money means that they can now lend more money out than was the case prior to their receipt of it?

5) Do you accept that all of the above processes will, unless there is a direct regulatory intervention, continue until all capacity to wring a return out of deposits received (within the fractional reserve requirements) is exhausted. In other words, until infinity is approached?

When you add up all of the liabilities and assets in the chart example I provided, it does not add up to £1000 due to the interest that has been added to the loans.

If you add up the fractional reserve held by all of the banks put together, it is there that you will find the original £1000 issued by the CB, spread out over the entire banking system's deposits held on account in the form of required fractional reserves. That being the case, where the **** do you think the £3000 in circulation came from? Oh, and of course, there is the interest of £600 that is due to be paid back as well (based on 5%). There has actually been £4000 lent out but, given that some of that money in circulation on that table ends back up as fractional reserves held on deposit account, if we subtract the £1000 held in the form of fractional reserves from the total amount of £4000 that has been lent out, this leaves £3000 actually in circulation being used by people as if it was base money which it is not.

In lieu of all of the above, I will ask you the same question I have asked you on previous occasions but which you have yet directly addressed other than via vagaries.

Do you deny that a given lender can add on to the deposit-side of its balance sheet, the debt-side of another lender's balance sheet and that the net consequence of this is that the same money gets re-lent out several times (in the example I have provided, based on the given fractional reserve ratio, three times. However, this will vary in real life depending on the fractional reserve ratio used)?

I have laid out the maths for you in a table. I have rendered that maths into language here for you. If you are going deny the existence of the money multiplier as outlined here, you should be able to say quite specifically where it is incorrect. No more obfuscatory bollocks if you please.

It's amazing how often you fall back to this response. You also like to play with false dilemma with your "Do you deny 'obvious fact'" gambits (often couples with some non-sequitirs). I'm now just curious to see if there is any answer I can give which will be accepted as one.stevecook172001 wrote:Bollocks

Lets try responding directly: Claims 1-4 are okay, claim 5 I disagree with but I don't particularly care about. Your unnumbered "Do You Deny" I do deny the net consequence (money is not re-loaned several times, it is loaned once, has a corresponding negative ledger entry and is then part of the money supply) but again I consider the point too trivial to really contest.

I do deny that this leads to exponential growth of the money supply. The reason, as has been patiently explained before, is that your model is incorrect in that it assumes that money paid as interest leaves circulation.

Please let me know if there are any other ways in which you would like me to repeat myself.

-

Little John

-

Little John

It is not sufficient to say you think any of those points are wrong. You need to explain why you think they are wrong or, as I said, your denials are bollocks.AndySir wrote:It's amazing how often you fall back to this response. You also like to play with false dilemma with your "Do you deny 'obvious fact'" gambits (often couples with some non-sequitirs). I'm now just curious to see if there is any answer I can give which will be accepted as one.stevecook172001 wrote:Bollocks

Lets try responding directly: Claims 1-4 are okay, claim 5 I disagree with but I don't particularly care about. Your unnumbered "Do You Deny" I do deny the net consequence (money is not re-loaned several times, it is loaned once, has a corresponding negative ledger entry and is then part of the money supply) but again I consider the point too trivial to really contest.

I do deny that this leads to exponential growth of the money supply. The reason, as has been patiently explained before, is that your model is incorrect in that it assumes that money paid as interest leaves circulation.

Please let me know if there are any other ways in which you would like me to repeat myself.

You have still not done that, so you are talking bollocks.

Additionally, I see you are playing the diversionary tactics again. Whether or not the money multipliers or, indeed, FRB in general, leads to exponential money supply growth or not is a related but directly unconnected question in relation to simply answering the question of whether or not the money multiplier exists.

...but that's what I want to say. I've talked about little else. Why push me into commenting on your model which I wasn't talking about and, by your own admission, is not directly connected to what I am talking about? I'm happy for you to contradict my opinions but not for you to contradict what my opinions are.stevecook172001 wrote: Additionally, I see you are playing the diversionary tactics again. Whether or not the money multipliers or, indeed, FRB in general, leads to exponential money supply growth or not is a related but directly unconnected question in relation to simply answering the question of whether or not the money multiplier exists.

I did briefly put down a couple of objections to your model, but again: it's not what I was actually disagreeing with you about so I don't want to be drawn into playing your straw man.